As an estimated 10 million Mexican free-tailed bats — nursing mothers and their young — began to form into a swirling gyre and rise on a gentle South Texas wind, a small crowd gathered on split-wood benches overlooking the slowly darkening Comal County cave for a lesson in bat ecology and political resistance.

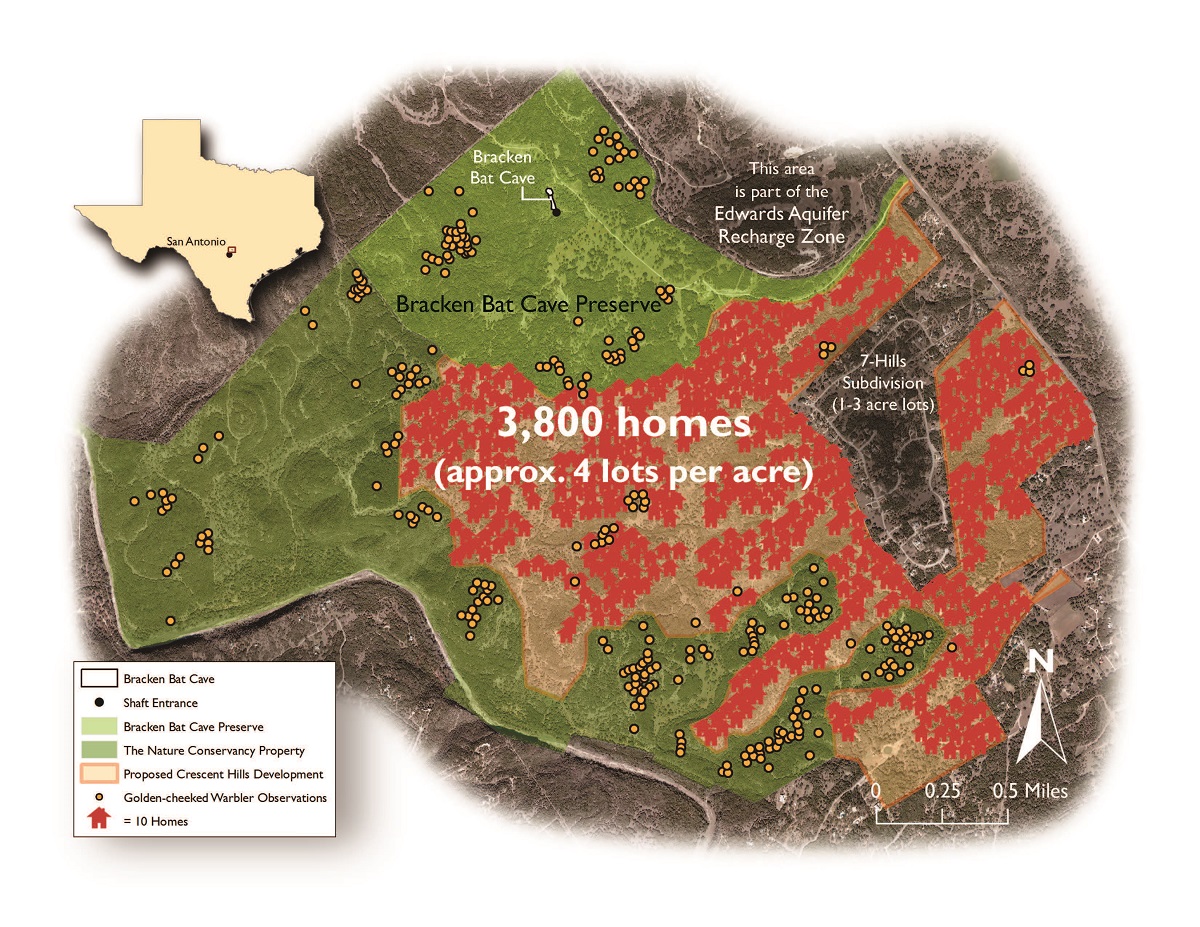

With the San Antonio Water System management’s endorsement and an elected city leadership reluctant to intervene, one of the planet’s biological treasures is about to face its most significant eviction risk in its 10,000-year residency. San Antonio developer Brad Galo has plans for 3,800 homes on the south edge of Bracken Cave Preserve, directly beneath the colony’s massive flight path.

While SAWS agreed in March to supply water lines to the site (and large enough ones to accomodate future tie-ins from piggy-backing development) so far only orange-ribboned survey stakes are in place.

Today, human bat allies cupped their hands to their ears to hear the jittery thrum of tens of thousands of mammalian wings in motion and inhale the equally impressive organic odor of this no-longer-secret hideaway. Children stopped fidgeting, possessed by a marval they hadn’t expected. The only sound is the throbbing of the wings and the occasional high whistle of a small furry body diving through the air like a bottle rocket back into the cave mouth.

Nearby air traffic controllers at Randolph Air Force Base were shutting down airstrip operations, says Fran Hutchins (above), Bat Conservation International‘s coordinator for Bracken Cave activities, as they do at 7 p.m. each night in order to avoid potentially costly collisions whenever the bats, which migrate seasonally back and forth between here and Mexico, are roosting at Bracken over the summer.

Click image for a slideshow of Friday’s Bracken emergence.

Doppler radar will start picking up the snaking bat traffic as the enormous colony — which takes four hours or more to fully evacuate the cave — makes their nightly run deeper into South Texas, says Hutchins. There they will engage another cloud darkening Doppler readings: equally dense fields of corn-earworm moths rising off their favored row crops in a slow summer march north toward Canada.

In fact, just this colony is believed to contribute to $800,000 in savings a year for South Texas growers by limiting the amount of pesticides needed and reducing crop damage. Nationally, bats are believed to save the agricultural sector $23 billion annually, he said. “And that’s at the low-end of the spectrum.”

“That kind of money doesn’t matter to politicians?” one woman, one of dozens who has come out on Friday’s summer solstice to learn how to fight off the development threat, asks.

“If you take it out of their pocket, it matters. But otherwise it’s out there in the ether,” said Hutchins.

But it’s not just the potential loss of economic aid to farmers that concerns BCI, human-bat interactions are sure to increase if the planned subdivision is built. Lights will attract insects to the homes, which will lure in the bats, particularly the young who tend to stay closer to home, leading to conflict. And curiosity seekers would become all-too inevitable as the distance between the bats and humans shrinks.

“You can imagine,” Hutchins tells us, “10,000 people — 4,000 9-year-olds? – we’re concerned with trespassing issues. This colony of bats has been here for 10,000 years. The guano is anywhere from 30 to 60 feet deep in the cave. Um, guano burns. If somebody was to come in and vandalize the cave, set it on fire, it’s going to burn for a long time. And we’re going to lose this roost space for this colony of bats and they’re not going to be able replace it quickly. There’s no other space in this area that large.”

San Antonio Mayor Julián Castro suggested to Texas Public Radio recently that he may be waiting on some kind of direction from the scientific community before getting involved. He said: “There is a science to figure out in terms of whether development would or would not actually harm the bats.”

Neither Castro nor any member of San Antonio’s city council have come out to view the bat emergence for themselves, Hutchins said.

A pair of state reps have, however, injected themselves into the conversation, with little success so far. As SA-based rep Lyle Larson told the Express-News earlier this month, “The bottom line is if we don’t do this right, we are setting up a really bad Johnny Depp movie,” he said. “The moral would be that humans did not understand the unintended consequences.”

And yet San Antonio has limited control, said Annalisa Peace, executive director of the Greater Edwards Aquifer Alliance, which is fighting the development for its position atop the porous karst limestone of the Edwards Aquifer’s recharge zone and potential to harm San Antonio’s drinking water.

What either SAWS or the City Council can do is immediately revoke the water deal, she said. And they can also push Galo, the lending agency, IBC Bank, and other parties toward a fair-market transfer of the Galo land for additional buffering around the preserve. So far, Galo has offered to sell 15,000 acres to BCI for the jaw-dropping price of $35 million, said Peace.

Still another danger is that the entire ordeal will be treated as if it were occurring in a vacuum. So far there is little indication that Castro or others in power see Bracken Cave as emblematic of global patterns that are already dismantling the planet’s very life-support system. In this era of interwoven global crises, it’s a prerequisite when it comes to understanding the value of nature and biodiversity in seemingly local development fights. And it’s a prereq for seeking higher office, too, Hutchins reminds us.

“If you believe the reports [Castro] has ambitions other than being a mayor,” Hutchins tells the group. “This is a minor problem compared to being president of the United States. So if you can’t deal with this minor problem compared to ecological problems dealing with the whole entire United States and the world, you might want to consider another job.

“The science is right in front of us,” he says, gesturing after the cloud of fluttering blackness. “These bats are flying right in the direction of the subdivision. You can’t argue with it.”